Atomic Structure

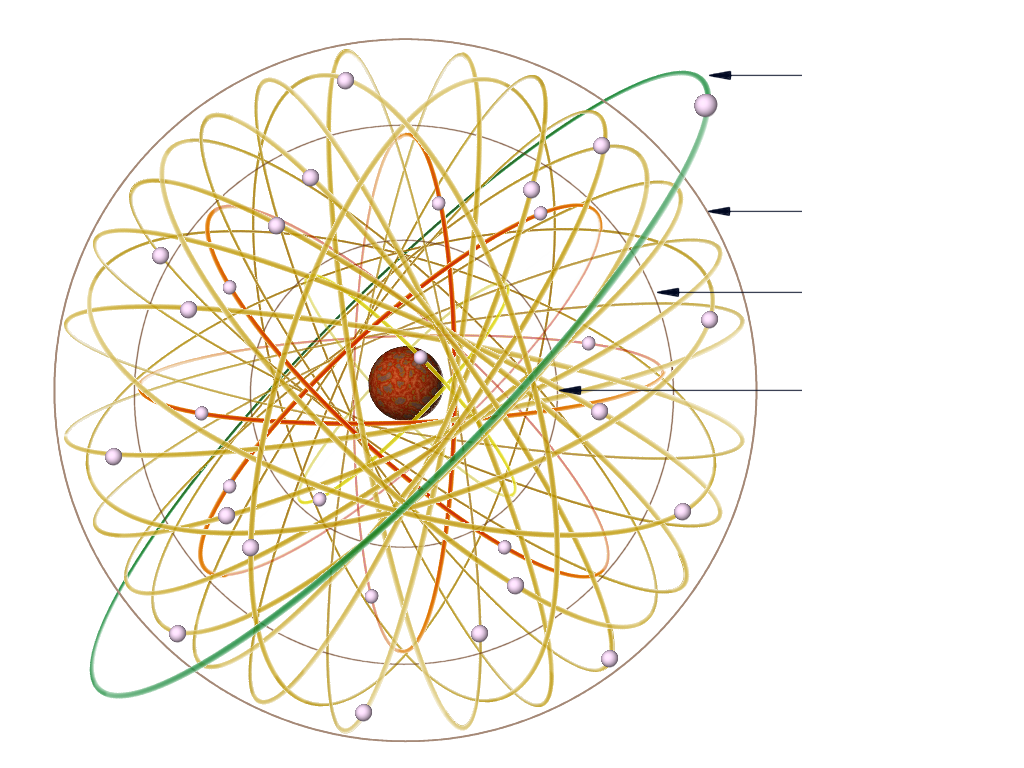

Figure 1: The composition of a simple helium atom (Rutherford–Bohr model)

Figure 1: The composition of a simple helium atom (Rutherford–Bohr model)

Atomic Structure

The atom is basically composed of electrons, protons, and neutrons. The electrons, protons, and neutrons of one element are identical to those of any other element. There are different kinds of elements because the number and the arrangement of electrons and protons are different for each element.

The electron carries a small negative charge of electricity. The proton carries a positive charge of electricity equal and opposite to the charge of the electron. Both the electron and proton have the same quantity of charge, although the mass of the proton is approximately 1,827 times that of the electron. In some atoms there exists a neutral particle called a neutron. The neutron has a mass approximately equal to that of a proton but it has no electrical charge.

According to theory, the electrons, protons, and neutrons of the atoms are thought to be arranged in a manner similar to a miniature solar system. Notice the helium atom in the figure. Two protons and two neutrons form the heavy nucleus with a positive charge around which two very light electrons revolve. The path each electron takes around the nucleus is called an orbit. The electrons are continuously being acted upon in their orbits by the force of attraction of the nucleus. To maintain an orbit around the nucleus, the electrons travel at a speed that produces a counterforce equal to the attraction force of the nucleus. Just as energy is required to move a space vehicle away from the earth, energy is also required to move an electron away from the nucleus. Like a space vehicle, the electron is said to be at a higher energy level when it travels a larger orbit. Scientific experiments have shown that the electron requires a certain amount of energy to stay in orbit. This quantity is called the electron's energy level. By virtue of just its motion alone, the electron contains kinetic energy. Because of its position, it also contains potential energy. The total energy contained by an electron (kinetic energy plus potential energy) is the main factor that determines the radius of the electron's orbit. For an electron to remain in this orbit, it must neither gain nor lose energy.

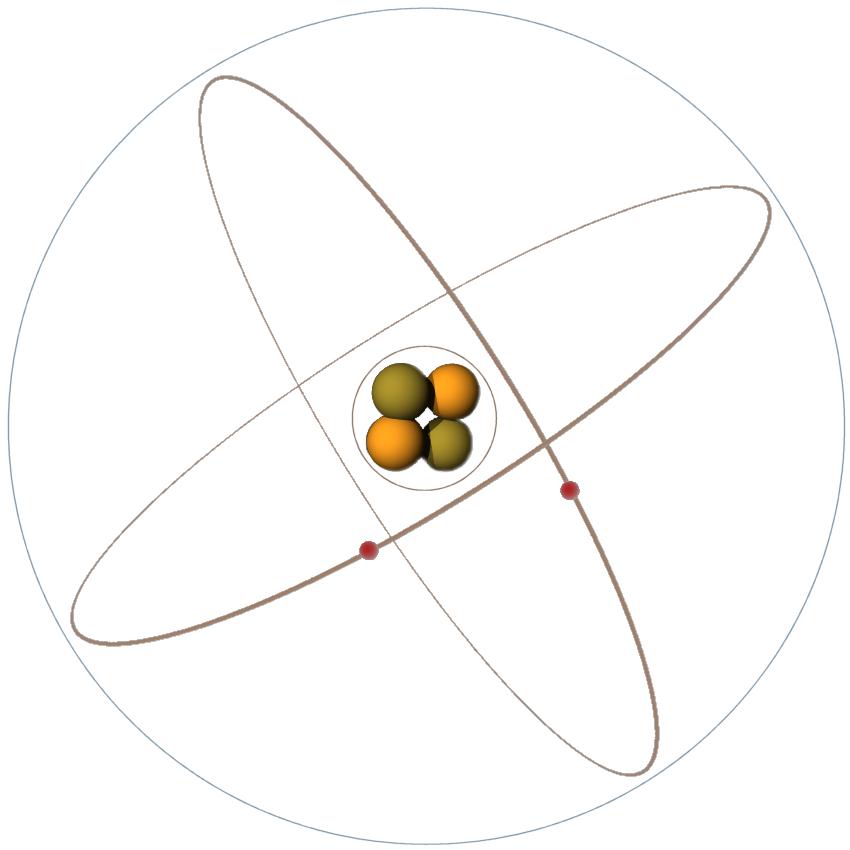

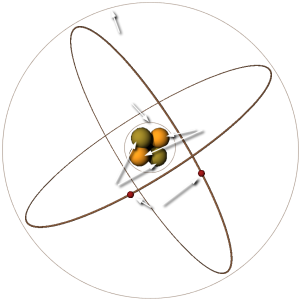

Figure 2: Copper atom (Rutherford–Bohr model)l

The orbiting electrons do not follow random paths, instead they are confined to definite energy levels. Visualize these levels as shells with each successive shell being spaced a greater distance from the nucleus. The shells, and the number of electrons required to fill them, may be predicted by using Pauli's exclusion principle:

| K-shell | 2 electrons | (n=1) |

| L-shell | 8 electrons | (n=2) |

| M-shell | 18 electrons | (n=3) |

| N-shell | 32 electrons | (n=4) |

Table 1: The number of electrons required to fill the shells

Simply stated, this principle specifies that each shell will contain a maximum of 2·n2 electrons, where n corresponds to the shell number starting with the one closest to the nucleus. By this principle, the second shell, for example, would contain 2·22 or 8 electrons when full. A list of all the other known elements, with the number of electrons in each atom, is contained in the Periodic Table of Elements. This periodic table of elements can be explanated physically with help of the „Bohr-Sommerfeld” theory of atomic structure.

Energy Bands

Orbiting electrons contain energy and are confined to definite energy levels. The various shells in an atom represent these levels. Therefore, to move an electron from a lower shell to a higher shell a certain amount of energy is required. This energy can be in the form of electric fields, heat, light, and even bombardment by other particles. Failure to provide enough energy to the electron, even if the energy supplied is just short of the required amount, will cause it to remain at its present energy level. Supplying more energy than is needed will only cause the electron to move to the next higher shell and the remaining energy will be wasted. In simple terms, energy is required in definite units to move electrons from one shell to the next higher shell. These units are called quanta (for example 1, 2, or 3 quanta).

Electrons can also lose energy as well as receive it. When an electron loses energy, it moves to a lower shell. The lost energy, in some cases, appears as heat. If a sufficient amount of energy is absorbed by an electron, it is possible for that electron to be completely removed from the influence of the atom. This is called ionization. When an atom loses electrons or gains electrons in this process of electron exchange, it is said to be ionized. For ionization to take place, there must be a transfer of energy that results in a change in the internal energy of the atom. An atom having more than its normal amount of electrons acquires a negative charge, and is called a negative ion. The atom that gives up some of its normal electrons is left with fewer negative charges than positive charges and is called a positive ion. Thus, we can define ionization as the process by which an atom loses or gains electrons.

gap

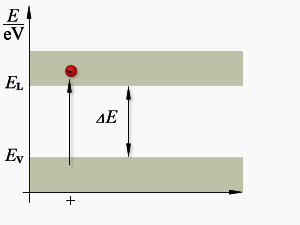

Figure 3: The energy arrangement in atoms

Up to this point, we have spoken only of isolated atoms. When atoms are spaced far enough apart, as in a gas, they have very little influence upon each other, and are very much like lone atoms. But atoms within a solid have a marked effect upon each other. The forces that bind these atoms together greatly modify the behavior of the other electrons. One consequence of this close proximity of atoms is to cause the individual energy levels of an atom to break up and form bands of energy. Discrete (separate and complete) energy levels still exist within these energy bands but there are many more energy levels than there were with the isolated atom. In some cases, energy levels will have disappeared.

Figure 3 shows the difference in the energy arrangement between an isolated atom and the atom in a solid. Notice that the isolated atom (such as in gas) has energy levels, whereas the atom in a solid has energy levels grouped into Energy Bands.

The upper band in the solid lines in figure 3 is called the conduction band because electrons in this band are easily removed by the application of external electric fields. Materials that have a large number of electrons in the conduction band act as good conductors of electricity.

Below the conduction band is the forbidden band or energy gap. Electrons are never found in this band but may travel back and forth through it, provided they do not come to rest in the band.

The last band or valence band is composed of a series of energy levels containing valence electrons. Electrons in this band are more tightly bound to the individual atom than the electrons in the conduction band. However, the electrons in the valence band can still be moved to the conduction band with the application of energy, usually thermal energy. There are more bands below the valence band but they are not important to the understanding of semiconductor theory and will not be discussed.

band

conductor

Figure 4: Energy level diagram for different materials

band

conductor

Figure 4: Energy level diagram for different materials

The concept of energy bands is particularly important in classifying materials as conductors, semiconductors, and insulators. An electron can exist in either of two energy bands, the conduction band or the valence band. All that is necessary to move an electron from the valence band to the conduction band so it can be used for electric current, is enough energy to carry the electron through the forbidden band. The width of the forbidden band or the separation between the conduction and valence bands determines whether a substance is an insulator, semiconductor, or conductor. Figure 4 uses energy level diagrams to show the difference between insulators, semiconductors, and conductors.

The energy diagram for the insulator shows the insulator with a very wide energy gap. The wider this gap, the greater the amount of energy required to move the electron from the valence band to the conduction band. Therefore, an insulator requires a large amount of energy to obtain a small amount of current. The insulator „insulates” because of the wide forbidden band or energy gap.

The semiconductor, on the other hand, has a smaller forbidden band and requires less energy to move an electron from the valence band to the conduction band. Therefore, for a certain amount of applied voltage, more current will flow in the semiconductor than in the insulator.

The last energy level diagram in figure 4 is that of a conductor. Notice, there is no forbidden band or energy gap and the valence and conduction bands overlap. With no energy gap, it takes a small amount of energy to move electrons into the conduction band; consequently, conductors pass electrons very easily.